Chicago Stories

Candy Capital

10/27/2023 | 55m 47sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Brach. Mars. Wrigley. Chicago was once known as "the candy capital of the world."

Brach. Mars. Wrigley. These are just a few of the candy companies that have called Chicago home. At the time of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, more than 100 candy companies were in operation in the area, producing such familiar confections as Baby Ruth, Tootsie Roll, Lemonheads, and Juicy Fruit gum. Audio-narrated descriptions are available.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Chicago Stories is a local public television program presented by WTTW

Leadership support for CHICAGO STORIES is provided by The Negaunee Foundation. Major support for CHICAGO STORIES is provided by the Elizabeth Morse Genius Charitable Trust, TAWANI Foundation on behalf of...

Chicago Stories

Candy Capital

10/27/2023 | 55m 47sVideo has Audio Description, Closed Captions

Brach. Mars. Wrigley. These are just a few of the candy companies that have called Chicago home. At the time of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, more than 100 candy companies were in operation in the area, producing such familiar confections as Baby Ruth, Tootsie Roll, Lemonheads, and Juicy Fruit gum. Audio-narrated descriptions are available.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Chicago Stories

Chicago Stories is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Chicago Stories

WTTW premieres eight new Chicago Stories including Deadly Alliance: Leopold and Loeb, The Black Sox Scandal, Amusement Parks, The Young Lords of Lincoln Park, The Making of Playboy, When the West Side Burned, Al Capone’s Bloody Business, and House Music: A Cultural Revolution.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- [Narrator] Coming up.

- [Joël] Chicago, more than any other city in America, truly embodies our nation's sweet tooth.

- And really, who doesn't like eating candy?

I mean, come on.

- [Narrator] Candy, crafted with love and an abundance of sugar is more than just a treat.

♪ There's so much milk in a Milky Way ♪ Candy won wars, built empires, and for nearly a century, it all came from Chicago.

America's candy capital.

- Chicago became the melting pot of candy.

- [Narrator] Chicago candymakers created some of the juiciest, stickiest, crunchiest, and most famous confections the world had ever seen.

- When it's good, it's good.

- If you're talking about Mars and Curtiss and Brach's, that's as big as it gets.

- Chicago had everything that was needed to make this industry explode.

- [Narrator] But an unexpected danger threatened the industry for survival.

- You could be crushed overnight.

- Tragically, you start to see a lot of great Chicago candy companies disappearing.

- Don't always be fooled by the sweet image, right?

There can be a real shrewdness in the candy business.

- [Narrator] The Candy Capital, next on "Chicago Stories".

(lively music) (lively music) (narrator) Walking into Margie's Candies on Chicago's North side is like stepping back in time.

In the dining room, customers indulge in a delightful array of old-fashioned favorites.

(diner laughing) But it's the kitchen where the old world truly comes to life, as each candy is lovingly crafted by hand.

- I'm making caramel.

After the caramel, we dip it with chocolate, either dark or milk.

Everything we make here is homemade and we do every day.

- So if we're going back to the turn of the century here in Chicago and visualizing the candy industry, you didn't have a lot of tools or technology to help.

It wasn't just pushing a button.

It was laborious work.

- Early candy making is so exciting to me because it's the hand expression of love.

- I really enjoy to make the caramel.

I love it.

I like to hear when people say your caramel is very good.

When people is happy, of course it made me happy.

(lively music) - [Narrator] Margie's has been in the business of keeping people happy since 1921.

When Greek immigrant Peter Poulos scraped together savings from shining shoes to open a sweets shop.

(lively music) When his son George took the reins, he renamed it after his sweetheart Margie.

100 years later, the Poulos family is still serving up treats and nostalgia, by hand.

(lively music) (narrator) In the late 19th century, waves of European immigrants, like Peter Poulos, came to the United States risking everything for a chance to rewrite their family's future.

- An experience like that is, it's just unbelievable that people were deciding that there is this country where you don't have to be impoverished for all the generations.

- [Narrator] And some were candymakers who made their way to Chicago with nothing but a suitcase, a recipe from their homeland, and a dream.

- These confectioners didn't only bring their ingredients and their know-how.

They brought their culture.

They brought their history.

That's reflected in the candy.

I mean, literally the copper pot becomes the melting pot of candy.

- The Germans had methodology for spinning sugar into cotton candy.

And the Italians brought what we call panning drums.

So those are the drums that make Jordan almonds.

That's a purely Italian thing.

- (Beth) Nougat from France, hard candy from England.

- You've got all kinds of immigrants who built enormous fortunes in the candy industry, and it tells you a lot about Chicago.

(lively music) - [Narrator] Fortune would eventually come for some.

But the building of Chicago's candy empire started at home in the family kitchen.

- In candy, anybody who had access to a stove and a recipe, right, could start a business.

I mean, that is the ultimate mom and pop.

- The woman would have a kettle there where she's processing chocolate and the little kids are running around it.

You can see they don't have to pay for babysitters that way.

- Candy as a business didn't require a huge amount of startup capital.

You can start with a good recipe and a kitchen, and a lot of the great Chicago candymakers did.

Great example being Ferrara Pan Candy Company.

- [Narrator] Today, Ferrara is universally known for iconic candies like Lemonheads, Red Hots, Laffy Taffy, and Trolli Gummies.

But this billion dollar empire of sweets all started with one man's desperate journey.

- My great-grandfather Salvatore Ferrara migrated here in the late 1800s, and he came to this country with literally nothing.

I can only imagine what it was like.

- [Narrator] At 17 years old, Salvatore Ferrara taught himself English, then found work as an interpreter with the Santa Fe Railroad.

(bell dinging) - Through that, he ended up saving enough money and started a bakery with his brother Giovanni, and his brother-in-law, Salvatore Lezza.

They had so much pride and they all dressed with dress shirts and ties, and then they had on an apron that made it look businessmen, but yet getting their hands dirty in a bakery.

Think about that: you're making cakes, cookies, confetti, which is the sugarcoated almonds you'd see at a wedding.

And what happened was that started taking off and they said, "Hey, we really can do something with this."

- [Narrator] The confetti flew out the door, and with that Ferrara Candy was born.

The family shop became a staple in the rapidly growing Little Italy neighborhood.

(lively music) But the largest ethnic community in Chicago was the Germans.

And their early forays into confections paved the way for Emil J. Brach.

- He was a very typical candy story in that, there's a number of candymakers who started out as traveling salesmen, but were really wanting to branch out on their own.

- [Narrator] After years of pounding the pavement, selling candy for other vendors, 45-year-old Emil Brach rolled the dice.

He invested his last dollars in himself and in the Brach name.

- He managed to scrape together a thousand dollars and told his wife, I'm starting a candy company.

And I'm sure she thought, "You're gonna invest all this money in a candy store."

I love the name, it was Brach's Palace of Sweets.

And it was located on North Avenue, which is right on the edge of the enormous German American district in Chicago.

Brach's used to have to print on their wrappers.

Please ask for B-R-O-X because a lot of Americans didn't know how to pronounce this German last name.

- [Narrator] Brach might have seen the potential for something much bigger, but even after a decade in the candy business, he was still a neighborhood confectioner, not a brand name.

- So at the turn to the 20th century, there were not the big brands for candy and chocolate that we think of today.

- They're licorice strips and suckers and peppermint canes, but none of it is affiliated with any particular company.

- Candy is sold mostly in bulk.

You know, you see those old wooden barrels where they would scoop out candy into a bag by the quarter pound or half pound.

(lively music) - [Narrator] Some candymakers found a way to expand their market to Chicago's wealthy class by portraying sweets as something exclusive, and a trip to the candy shop as a glamorous escape.

- Traditionally, sugar was a really expensive thing, so you saved it for special occasions.

That's why we have wedding cakes and cakes on our birthdays.

- Candy was a bit of a luxury item, and you have places where people could go and you know, enjoy a little sweet.

They oftentimes were very deluxe.

So if you went to a confectionary shop like Allegretti or Gunthers, it would've been a special night out.

- [Narrator] That image of luxury is exactly what Charles Gunther hoped would attract an upscale clientele to his shop.

- It was a fantastic space, stained glass window, marble counters, and located right in the downtown district.

- [Narrator] Gunther was one of the first candy moguls, but his shop was destroyed in the Chicago fire of 1871.

He quickly rebuilt and stocked his counter with a trendy new treat, caramel.

- Caramels were not invented in Chicago, but Gunther is often credited with the mass popularity of caramels in the 19th century.

- (Beth) Caramel at its essence is cooked sugar.

And as soon as you get it close to your nose, you're gonna smell that beautiful cooked sugar, maybe a little bit of dairy, you know, fresh dairy cream.

When it's good, it's good.

- And to give you a sense of the scale of his success, Gunther used a lot of the fortune that he made selling candies to buy up Civil War artifacts.

He bought a prison from the Civil War and shipped it to Chicago, but it laid the foundation for Chicago to be home to one of the greatest collections of Civil War artifacts.

We have a candy guy to thank for that.

- [Narrator] Gunther's caramels and collection were the envy of the city, but the image of candy as an elegant extravagance seemed to clash with Chicago's rough and tumble blue collar reputation.

- I thought about Chicago as being this place with meat packing, and it's known for the stockyards, and it's known for steel, and these are these big important industries.

And then you've got candy.

(lively music) It just seems, it seems frivolous, but boy it's not.

(lively music) - [Narrator] At the turn of the 20th century, candy was poised to move beyond sweet indulgence and become big business in Chicago.

But of all the industrial joints, in all the towns, in all of the world, why Chicago?

- I don't think candy came to Chicago by saying, you know, "We want Chicago to be the focus."

It was a necessity.

- [Narrator] Chicago was the railroad hub of the United States.

It was easy to get commodities in, easy to get product out.

And its central location put Chicago in close proximity to raw materials.

Dairy from Wisconsin, corn syrup from Iowa, and sugar beets from Michigan.

- Whatever the sugar beet is, I thought sugar comes from canes and you whack it down like this.

- The sugar beet is where most of the world's sugar comes from today.

- It's kind of looking like a giant radish and they grow as a vegetable, I guess.

- [Narrator] Before the sugar beet, candymakers everywhere used cane sugar, which only grew in warmer climates and was often harvested by slaves.

- Certainly a lot of the confectionary ingredients have sugar and chocolate, have a dark past.

Meaning, you know, sugar was part of the slave trade, as was chocolate.

- [Narrator] Abolitionists wanted a substitute for cane sugar, and eventually farmers turned to the sugar beet.

The crop could survive colder climates, which in the early 1900's was a necessity for any candymaker.

- If you are pre-refrigerated truck era, and you need to get a delicate product susceptible to melting, maneuvered, and created, and manipulated, and shipped, what better place than a city that's cold nine months out of the year some years, Chicago.

- [Narrator] Thanks to Chicago's wonderful weather, rail network, and workforce, the right candy making ingredients were in place.

But there was still something missing.

Confectioners needed to get their products out to the world, and as luck would have it, the world was about to come to Chicago.

(lively music) - So in 1893, you want entertainment, you are going to the Columbian Exposition because that's where it's at.

- [Narrator] The World's Fair was a celebration of cultures from across the globe.

It was a place to showcase the latest achievements and technologies, including one device that would take chocolate in a new sweet direction.

- In the history of inventions, mankind invented the submarine, the photograph camera, and the machine gun before anyone figured out how to mix milk and chocolate to create milk chocolate.

- [Narrator] Enter German engineer, J.M Lehmann.

His machinery for processing bitter dark chocolate into sweet milk chocolate, amazed scores of fairgoers, including one caramel maker from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Milton Hershey.

- At the World's Fair, everything changed because that aroma with that deep, delicious chocolate odor, imagine if you'd never smelled that before, and he never had, because it didn't exist.

And he walks into this booth and he is wowed.

He immediately recognized chocolate was the future.

- [Narrator] Milton Hershey was so captivated that he offered to buy Lehmann's machinery on the spot and had it shipped to Pennsylvania.

- I don't want to say it was called nowhere, Pennsylvania at that time, but it was not yet called Hershey, Pennsylvania.

He took the chocolate making equipment back and started dipping his caramels in chocolate.

- But it's not just the machinery, it's also the introduction of new candies at the World's Fair.

And this idea of branded confections.

- [Narrator] Immigrant brothers, Frederick and Louis Rueckheim sold their version of caramel covered popcorn and peanuts, which they called Cracker Jack.

And Chicago socialite and hotelier, Bertha Palmer enticed fairgoers with a debut of the brownie.

- [Beth] At that fair, it was like candy went from black and white to color.

- People were now getting a sweet tooth, or in some cases more than one tooth.

So by getting a taste for these treats at the fair, this primed the path for even bigger business.

- [Narrator] Now, everyone wanted a piece of Chicago candy, but in order to keep up with demand, small entrepreneurs like Charles Gunther, Emil Brach, and Salvatore Ferrara needed to pump up production.

So they took a cue from Henry Ford, another industrial giant who already laid the blueprint for producing at scale.

- Ford is starting his assembly line, and Ford begins to manufacture Model A's and Model T's and candymakers took notice and they said, "Can we make candy in huge batches in an assembly line fashion?"

To go from the kitchen to the factory is an enormous leap, and the ones who were successful were the ones who were able to do that.

- Suddenly, if you've got machinery, the quantity of candy that you can make is vast, it's just huge.

- Hello?

(audience laughing) - Well, when I think of the inside of a candy factory, I think of the classic "I Love Lucy" clip, where Lucy and Ethel are out to prove that they can succeed in the working world.

Now their job is to wrap the candy.

- Oh, this is easier.

- Yeah, we can handle this okay.

- But what happens if the conveyor belt starts to go faster and faster and faster?

Well, comedy gold is what happened.

(audience laughing) - [Narrator] As the industry grew, so did the workforce.

More than 25,000 men and women found jobs at the height of the factory boom.

- It's not the slaughterhouse, it's not the steel worker.

It is cooking, it is food, and it is delicious.

- By no means was this a utopian factory.

But given these options, a candy factory was, I want to say, a sweet place to be.

It was certainly a decent place to be.

- [Narrator] By 1929, Chicago's candy manufacturers saw sales climb to more than 65 million dollars a year.

- And so a lot of confectioners realize this can make people rich, this can make people famous.

And so I think it was this tantalizing combination where if you're an entrepreneur and you look at that business, it's pretty seductive.

- [Narrator] And who could resist?

Many attempted to break into the industry, but the candy capital was no place for the timid.

Success there called for a special type of character.

- Candymakers can be so clever, don't always be fooled by the sweet image, right?

There can be a real shrewdness in the candy business.

- [Narrator] And no one understood the potential quite like William Wrigley Jr. A defiant child, Wrigley was kicked out of school at age 11, but soon discovered he had a knack for sales.

- William Wrigley Jr. is one of those great American success stories.

Came to Chicago in the early 1890s, and the legend is he had $32 in his pocket or something, but his father was a soap manufacturer, so he starts going door to door selling soap.

- [Narrator] But the soap wasn't moving.

So the young salesman offered a gimmick, a free can of baking powder with every bar of soap.

- The baking powder became more popular than the soap, so he dropped the soaps, sold baking powder, eventually started offering other premiums, including gum with every order.

- [Narrator] Just like before, the gum outperformed the baking powder.

And voila, the Wrigley empire was born.

- But it's such a perfect example of what William Wrigley did really, really well, which was innovative marketing.

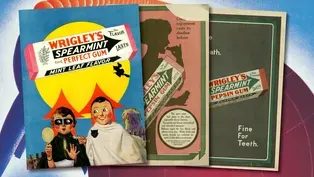

- [Narrator] Wrigley bought out his gum supplier and started developing his own flavors.

First came Juicy Fruit.

Followed by Spearmint.

And eventually Doublemint.

The new brands earned millions.

And the company rallied around Wrigley's marketing motto, "Tell them quick, and tell them often."

- When you look at the Wrigley's ads, he was using bold graphics, bright colors, minimal text.

It was very innovative when a lot of advertisements were very text heavy and told whole stories.

You'll see early Wrigley's ads and they'll say, "It aids your digestion."

I'm not sure we would use that today, but it worked.

And then of course, he had these great stunts.

You know, he one time said he wanted a mile wide Wrigley billboard, so he bought up 117 billboards between Atlantic City and Trenton just for Wrigley's ads.

And mailed a packet of gum or sticks of gum to anyone who had a listing in any 1915 United States telephone directory.

You know, if you can afford a telephone, you can afford gum.

- [Narrator] William Wrigley took his company public and by 1919, the business he had started with a humble pack of gum was worth 12 million dollars, more than 210 million in today's dollars.

Wrigley cemented his place in the Chicago skyline with his iconic headquarters on Michigan Avenue and even bought his own island, Santa Catalina, off the coast of Southern California.

- And then he made a dreadful error.

He bought the Chicago Cubs.

His accountant should have committed him to an insane asylum.

Being a Cubs fan is you have to worship losing.

When you make bucks in America, the next thing you think is, "What am I gonna be remembered for?"

He's got a tower, so he must be something.

He's got a baseball team, so I better buy his gum.

(lively music) - [Narrator] Wrigley flourished at the dawn of the Roaring Twenties, and he wasn't alone.

The First World War had ended and consumerism had the US economy running at full speed.

The candy capital had to keep up.

- EJ Brach developed his own wrapper that could wrap candies automatically.

By doing that, he took the industry in a whole new direction.

- And that ultimately leads to the enormous Brach's factory on the west side.

To think about a factory where you can make 250 different kinds of candy, mind-boggling, compared to the typical candy operation in the 19th century.

(lively music) - [Narrator] The candy business in Chicago was booming and Uncle Sam was about to give the industry an even bigger boost.

- [Announcer] World War I is over and so are America's days of legal alcoholic drink.

- [Narrator] Prohibition outlawed the production and sale of alcohol, and with the nation dry, Chicago emerged as a hub of bootlegging and organized crime.

While some Americans sought out speakeasies, others turned to candy.

- And so there were many breweries and saloons and bars in Chicago who decided, "Okay, if we can't sell liquor openly and legally, what can we do with all of our real estate?

We can sell candy, we can open ice cream parlors.

- [Narrator] Candy sales jumped.

And ice cream, candy's confectionary cousin, saw a 50% increase in consumption.

All thanks to prohibition.

(lively music) - I think it was a very vibrant and fun time for the companies.

They were making good money.

They were growing at a pretty good rate.

- [Narrator] Confectioners created all sorts of new brands and dreamed up clever candy names like Bit-O-Honey, Oh Henry, and Milk Duds.

- Milk Duds, what they really wanted was a perfectly round chocolate-covered caramel, but the machinery kept turning them out kind of flattened.

They were duds, so they took the name as a little bit of an in joke, milk chocolate duds.

(lively music) often times there were candies named after national crazes, like Brach's had the Swing Bar, and Bunte Brothers for a long time had a bar called the Tango.

They're riffing on national crazes, they're riffing on celebrities.

Lion Candies had a Lindy bar named after Charles Lindberg.

- [Narrator] Aviator Charles Lindberg had gained worldwide acclaim and adoration for completing the first nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic.

His popularity was a bankable asset.

- I don't think he got any royalties on it, but these are names that are memorable and they help these brands stand out at a time when that was a really new approach for selling candy.

- [Narrator] One candymaker took extreme measures to avoid paying royalties.

- Baby Ruth.

The Curtiss Candy company always said it was named for Ruth Cleveland, beloved daughter of Grover Cleveland.

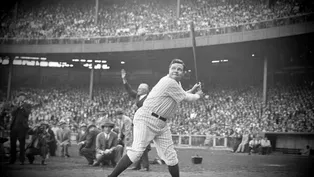

Historians are a little bit skeptical, and it seems a little ironic that Babe Ruth, the baseball player, was hitting his peak fame around 1920.

- [Narrator] George Herman "Babe" Ruth was the most sought after babe of the era.

The New York Yankees slugger had captivated the nation in 1921 by hitting a major league record, 59 home runs.

- The Baby Ruth name might have been a way to at least tap into the popularity of the baseball player without paying royalties to Babe Ruth.

- [Narrator] And the Babe Ruth controversy showed the gusto it took to make candy stand out.

And that brash attitude at Curtiss Candy was all thanks to founder, Otto Schnering.

- I remember a factory on the Chicago River that used to be there, that giant Baby Ruth logo on it.

He was really building on William Wrigley's idea of tell 'em quick and tell 'em often.

- Otto Schnering created a character called NRG, N-R-G, who really promoted the concept that eating a candy bar was good for you and would give you energy.

- So he would do these metabolism tests.

You know, how far can a man run on the muscle fuel in one Baby Ruth bar?

And it turns out to be like 1 and 5/6 miles.

I don't think anyone's running 1 and 5/6 miles by eating a Baby Ruth bar.

But it's conveying this idea that when you need a jolt of energy, have a Baby Ruth bar.

- [Narrator] Less than two years after the release of Baby Ruth, Otto Schnering hit another home run with Butterfinger.

- And so Butterfinger, one of the things that makes it really interesting is not only is it coated in chocolate, but it's got kind of air pockets in it, and then these little bursts of peanut butter.

It's kind of fabulous.

- All these new tweaks, really big innovations in marketing candy, in advertising candy, they were enormously influential and influential nationally.

- That stops bad breath.

- And candymakers in Chicago needed it because there was a lot of competition there.

- [Narrator] And no one embraced that competition quite like Forrest Mars.

But his rise to the top of the candy capital began with a rocky start.

- So Forrest is making his way through the world as a salesman.

His job is to plaster the streets of Chicago with posters for Camel cigarettes.

And you can imagine that did not go over very well with the local business community.

Forrest found himself arrested and put in jail.

Who comes to bail Forrest out, but his father, who he's never met.

- [Narrator] Forrest's father, Frank Mars, was a middling confectioner from Minneapolis.

- Frank Mars divorced Forrest's mother Ethel when Forrest Mars was a baby.

And Forrest grew up not knowing who his father was, not knowing that his father was a candymaker.

- [Narrator] Frank had generated modest sales with the whipped cream filled Mar-O-Bar, but had gone bankrupt twice in the early 20th century.

This impromptu family reunion would change the course of Mars history.

- That afternoon after being bailed out of jail, the two men sit down and they get to meet each other for the first time.

And Forrest Mars is drinking a malted milkshake.

And supposedly he says to his father, "Hey dad, if you really wanna make a great candy, take this flavor of malted milk and put it inside a candy bar."

And at that moment, that was the idea that led to his father going back to the candy company in Minneapolis and creating his most famous bar, the Milky Way.

- [Narrator] Fresh off the success of Milky Way, Frank invited Forrest to join the family business.

Together, they moved the Mars headquarters from Minneapolis to Chicago in 1929, and built a sprawling new factory on the west side.

- Well, if you look at it from the street side, it doesn't look like a factory at all.

- And that was all Forrest Mars's idea.

Secrecy was incredibly important to him, and he did not want anybody peering inside that factory.

So he proceeded to decorate the outside of the factory like a Spanish monastery.

- [Narrator] Mars christened the new factory by releasing what would become one of the biggest candy bar brands of all time, Snickers.

- It's got sweet, it's got sour, it's got salty, it's got bitter, and it's got umami.

If I was to pick, you know, one food that sort of was like the perfect consumer packaged good, Snickers would be up there.

- Well, I recently tasted a Snickers bar and it tasted exactly like the Snickers bar that I had in childhood.

And I must say I loved that concept of continuity, that there's something dependable that you can always go back to.

- [Narrator] The father and son duo continued their hot streak when they followed Milky Way and Snickers with 3 Musketeers.

- 3 Musketeers.

I mean, my mouth waters just saying the words.

♪ 3 Musketeers, the double chocolate treat ♪ - If somebody was looking for me at the paper and my desk was empty, somebody would say, "Oh yeah, it's two o'clock, he's at the candy machine.

He needs his 3 Musketeers."

- [Narrator] The new candy bars pushed annual sales to 32 million dollars in 1932.

But the lucrative run for the Mars Company came at a cost to the Mars family.

- Their relationship is very difficult because Forrest firmly believes that he's a better businessman than his father.

Forrest wanted to make it a global business.

Nobody is thinking global at this time.

For Frank, he has made an enormously successful company.

He's driving around in a Duesenberg, he's living the life, and here comes this upstart kid telling him, "You're not doing anything right."

So he offered Forest $50,000 and said, "Take the recipe for the Milky Way, I don't wanna have anything to do with you.

You take the money and make your own company."

- [Narrator] Forrest was determined to make a name for himself.

He took the cash buyout and set off for the other side of the Atlantic.

- And it's kind of a sad story because Forrest, he moves to England and he's not abroad for nine months, his father suffers a massive heart attack and dies.

- [Narrator] Frank Mars was dead at the age of 50.

Control of the Mars Company went to Frank's second wife.

- I think Forrest always wanted to prove to his father that he could be successful.

He wanted to earn his dad's love.

And when his dad passed away and that opportunity was lost, I think it really killed something in Forrest.

- [Narrator] But it didn't kill his ambition.

Forrest went in search of a product that he could call his own, even as the world descended into a Great Depression.

- [Announcer] Our greatest primary task is to put people to work.

(gentle music) - [Narrator] During the Depression, Americans endured new hardships, including rampant homelessness, hunger, and vast unemployment.

Candy sales dropped, but so did the cost of sugar and cocoa.

Confectioners weathered the storm by keeping their products cheap.

- Maybe families couldn't afford all of the necessities that they once had, but they could still afford that 5 cent candy bar.

- When you look at Chicago during the Great Depression and you see the marketing of candy as meal replacement.

- The Chicken Dinner bar, for example, sort of might not sound as appetizing to us as, let's hope, it did to people then.

But the message was clear that if the real chicken dinner wasn't on the table, here's an alternative.

- [Narrator] Even one of Chicago's legendary department stores turned to candy to help struggling retail sales during the Depression.

- Frango Mints were actually invented in Seattle at Frederick & Nelson Department store.

And when Marshall Field's bought Frederick & Nelson it got the right to the term Frango.

When it was first introduced, it was $1.50 a pound, which was a lot for a box of chocolates.

But because it was so exclusive to Marshall Field's, it becomes this sort of portable symbol of Chicago.

For visiting out of towners, bring a box of Frango Mints.

- [Narrator] It might have been a novelty to make candy in a department store, but by 1940, Chicago confectioners produced over 550 million pounds of candy per year.

Nearly 40% of all candy in the United States came from the candy capital.

It looked like nothing could stop the momentum.

(lively music) (engine revving) (bomb booms) - [President Roosevelt] December 7th, 1941, a date which will live in infamy.

- [Narrator] When the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the US into World War II, the nation's focus turned to supporting the troops and the candy industry hit a crossroads.

- What happens is that a lot of candy companies start putting a big percentage of their production towards military rations.

A lot of companies couldn't supply the civilian market as well as the military.

Wrigley's is maybe the most famous for this.

They put out billboards that said, you know, remember this rapper, we will be back when the war is over.

You could look at certain soldiers, the 1943 soldiers K ration had a stick of Wrigley Spearmint gum for breakfast and lunch and dinner.

- [Narrator] Candy in war rations was something Forrest Mars had seen just a few years earlier.

Now he realized this was the opportunity he had been looking for.

- While he was in Europe, he saw that the Spanish soldiers were eating little lentil-shaped chocolates that were coated in candy and they didn't melt.

And Forrest was utterly fascinated.

He knew that was the product that he was gonna introduce to the American market.

- [Narrator] One small problem, Forrest didn't have any chocolate and he was persona non grata at Mars.

So he showed up on the doorstep of his family's number one competitor, Hershey.

- Unannounced got a meeting with the man who was the president of the company, William Murrie.

And he tossed some of these candy-coated chocolates onto Murrie's desk and he said, "This is the future.

These chocolates don't melt, and I want to start a company."

That is what the M on the M&M stands for, Mars and Murrie.

(lively music) - [Narrator] Forrest had what he needed, a pipeline to Hershey's chocolate.

Soon M&M's were in the hands of American soldiers around the world.

- Once he had secured that, he made Murrie feel like a total peon.

He never consulted with Murrie on anything.

- [Narrator] The partnership was short-lived.

Forrest bought out Murrie's share for 1 million dollars.

- In the end, the only thing that the Murrie family had to show for this joint venture was that M on the M&M.

(footsteps pattering) - During World War II, candy becomes very closely identified with patriotism.

- Have you ever seen a picture of allied troops coming into a town and not handing out chocolate?

You see a little kid, you're gonna give them the candy.

- [Narrator] Candy consumption ballooned to 28.5 billion pounds per year in post-war America.

That's over 20 pounds per person.

But Forrest Mars struggled to transition his M&M's from military novelty to the mass market.

- And so he hires an advertising firm.

And sure enough, discovered kids would choose M&M's over every other candy bar on the market.

There's only one problem: kids don't hold the purse strings.

- [Announcer] M&M's chocolate candies.

The milk chocolate melts in your mouth, not in your hand.

- Melts in your mouth, not in your hands.

And he knew that that slogan would capture mom's attention.

And it sure did.

Within three years of that ad campaign, M&M's was the number one candy in the country.

- [Narrator] Candy was ready for primetime.

♪ Double your pleasure, double your fun ♪ ♪ Double pleasure is waiting for you ♪ - I'm willing to bet a lot of people are gonna know that song.

- My mother loved Butterfingers and they make me think of "The Simpsons" now.

- Looks like you could die of malnutrition, dude.

- [Narrator] Peanut buttery Butterfinger.

- It's neato.

- And it's neato.

- [Narrator] And who could forget the wise old owl?

- Tootsie Roll Pop.

It's coming back to me.

But there was a hook, there was a key, wasn't there?

What was it?

- How many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie Roll Pop?

- Let's find out, one, two, three.

(Tootsie Roll Pop crunches) Three.

- It's a sort of incalculable distance because soon you just bite it and chew it, or was that just me?

(laughs) - A lot of people think Tootsie Rolls were invented in Chicago, but actually they were invented way back in 1896 in Brooklyn.

(lively music) - [Narrator] Tootsie Rolls were invented by Leo Hirshfield and made in New York for over 70 years.

Then, in 1968, company President Melvin Gordon, moved the operation to Chicago and set up shop in a former World War II bomber manufacturing plant.

(lively music) Since 1975, Tootsie Roll has flourished under the watchful eye of Gordon's wife, Ellen Rubin Gordon.

- She's remarkable.

When Ellen Gordon was 18, her father put her in a Tootsie Roll ad.

This is when he was president of Tootsie Roll.

Who would've known that someday she would be at the helm of Tootsie Roll.

And she's significant because she was one of the very first women to head up a company being traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

- [Narrator] In 1963, Chicago's candy output was double New York, its nearest competitor.

As for Mars, when Frank's second wife died, Forrest inherited half of her stock, and within a few years he acquired a majority share.

In 1964, he named himself CEO.

The family business was finally Forrest's.

- So Forrest's business principles, I think were extraordinarily ahead of their time.

His understanding that a brand would have to be recognized worldwide.

Forrest, from the beginning, had that vision.

- [Narrator] Forrest Mars's relentless drive transformed the family business into a global empire worth tens of billions of dollars.

Forrest amassed a personal fortune, and in 1999 was named the 30th richest man in America.

- He had a very difficult personality, very exacting, not the kind of boss that you would really wanna work for.

He basically said, "Yeah, I'm a bastard, but I'm driven and this is our goal.

And if you wanna get on board this train and work your heart out, I'll pay you.

I'll make it worth your while, but you have to be just as dedicated as I am."

And he got that out of his workers.

Truly tremendous.

- [Narrator] Mars and Chicago's other candy royalty were at the peak of their powers and confident in their plans for succession.

Ferrara Candy, the family firm that began in a Little Italy bakery, boldly opened a new factory in the suburbs.

But their proudest moment would prove to be bittersweet.

- My great-grandfather had been ailing.

He had heart issues.

And when they had purchased that building, they didn't tell him yet.

My grandfather wanted to show his father, and sadly, my great-grandfather died right before the sign was put up, and he never knew about that next big plant.

- [Narrator] Despite this family tragedy, Ferrara confidently blazed a path in panned candies.

- There's two types of pans.

There's hot pan and then there's cold pan.

In the hot pan, it's a copper tumbler, okay?

And underneath it are Bunsen burners with flames.

- [Narrator] Think Jawbreakers or Atomic Fireballs.

- The cold pan process is, you got all your tumblers rolling and you slowly add sugar, flavor, corn syrup, and it comes out looking like jewels.

- [Narrator] Like Lemonhead and Alexander the Grape.

- When the third generation came in, my grandfather says, "I want to tell you something, you're getting in here, okay?

We expect you and your generation to take it to here."

Well, like I said, they were here, they expected it to here, and that generation, they took it through the roof here.

And that was gummies.

Once that happened, that was the boom.

- [Narrator] Ferrara rode the gummy boom all the way to an estimated 324 million dollars in annual sales.

But there was a danger lurking in the industry.

A drastic change was coming for a critical ingredient, and it was about to send shockwaves throughout the candy capital.

- My uncle Jimmy would go with my grandpa every year to these forums, and it was about sugar, where it's going.

Because at the end of the day, if your sugar prices are outta whack, you're outta business, like it's overnight.

- This legislation will help put America's farmers back into a competitive position in world markets.

(audience clapping) - [Narrator] The 1981 Farm bill created a series of subsidies that protected sugar farmers from foreign competition.

But with fewer suppliers available, the price of sugar skyrocketed.

- We have to buy US sugar, and US sugar is probably 10 to 20 cents a pound over world sugar.

- But you see people shutting down all over the place.

This guy's struggling, this guy's struggling, this guy's struggling.

And these people were people to us, they weren't companies.

- And everything became more expensive.

We had companies moving operations to Canada, Mexico, China.

- [Narrator] For the first time, candymakers were forced to explore life outside Chicago.

- We had the original founders, they kind of grew up in age and they were maturing.

The second generation or the third generation were coming in to run the businesses.

And I think they maybe had different philosophies and the bottom line had to be increased.

Follow the money, and you can usually get a decision as to why people did what they did.

- [Narrator] Eventually, Chicago's candy families faced the most painful decision of all, endure the rising costs and try to hang on or sell out and end their dynasties.

- Consolidation really became the name of the game.

- But really tragically, you start to see a lot of great Chicago candy companies disappearing because the brands are purchased by other corporations.

- [Narrator] By the early 2000's, most confectioners had merged, relocated, or shifted production away from the candy capital.

The final blow came courtesy of a Hollywood blockbuster.

- Oh gosh, it's the imploding of the Brach's Administration building in "The Dark Knight".

- [Narrator] The Brach's factory was once the largest in the world, employing more than 4,500 people.

But in 2008, the defunct plant made a memorable cameo in "The Dark Knight".

(bomb booms) - Brach's sort of played the role of Gotham City Hospital.

In this moment, there's this massive explosion and this fireball.

(bomb booms) It's a fabulous moment and it's also a really, really sad moment for anyone who absolutely adored Brach's.

- [Narrator] The last empire standing was Mars.

The family firm started by Frank Mars and shepherded by Forrest Mars.

In 2008, Mars purchased Wrigley for 23 billion dollars and became the largest candy manufacturer in the world.

- I mean, at this point, Mars and Wrigley, that's one company.

And so it was sort of natural in the end that the two biggest candy firms in the United States would join forces, and they have.

- But those brands, they don't have that family vibe anymore.

They don't have that family knowledge.

They just become a brand that you can buy at Costco.

- Nobody who inherits a family business wants to be the one to oversee the end.

If you look at the history of family businesses as a whole, it's virtually impossible to maintain family ownership into the fourth generation.

You have too many cooks in the kitchen and too many people who wanna run the show.

And that's usually the point of failure.

It's kind of sad.

- My father on top, Salvator Ferrara the second, my grandfather, Nelo V. Ferrara, and then myself.

My first job was there, I was 15 years old.

My grandfather goes, "Come with me, son."

Brings it right by the stairwell.

He says, "Emilio, put him to work."

And that was it.

I never wanted to work other than with my grandfather and next to my dad, and I'd got to do it for a number of years.

It's who you are, it's where you come from, it's what you're made of.

This was family, home.

(gentle music) (machine whirring) - The rollers are chilled because there's a lot of heat being generated during the grinding.

- I hate using the word I. I think it's more like we.

We started working on, and I helped create the product that's still pretty successful.

It's called Nerds.

(Nerds crackling) If you're under probably 15, most people know what Nerds are.

- [Narrator] Candymaker Bob Boutin has spent his career inventing sweet treats that continue to delight children and adults alike.

- I've really enjoyed it.

I mean, it's a great industry with a lot of very nice people, company presidents, entrepreneurs.

Every once in a while I start talking about some old people that I work with.

- It's right here.

- I choke up, I'm sorry.

But there's the personal satisfaction of seeing something that you've been involved with, making someone else happy or pleased and be successful.

So that's the fun part.

You know, what we see now, it's interesting, is the candy industry is evolving.

The big companies got bigger, some of them imploded, some of them sustain, but the ones who imploded left voids.

Those voids are now being picked up by the more smaller entrepreneurs who are now growing to be mid-size companies.

So it's this kind of a circle of life for candy too.

(lively music) - [Narrator] As the big corporations play on the world stage, a handful of rising stars set out to carve a candy path in Chicago, just like so many before them.

(lively music) - So Stephanie Hart is an amazing Chicago entrepreneur.

She is such a gifted baker.

Her caramel cake, oh my goodness, is delicious.

And she recently had the opportunity to purchase Cupid Candies, which is a well-known local Chicago factory.

And so I love the idea that an up and coming entrepreneur can make her artisanally crafted goods in this grand Chicago historical space.

- We are so excited to be part of the Candy revolution in Chicago.

It's not dying.

We are very much alive, and very much making chocolate on the south side.

This is one little factory that didn't pack up and go someplace else, so I feel very connected.

- We're seeing the craft chocolate movement.

There was craft beer, craft coffee, craft chocolate had to be next.

And craft chocolate is going back to the roots in the sense of hand crafting, and yet it's also pushing the market forward.

- [Narrator] For nearly a century, Chicago reigned supreme as the candy capital of the world.

- It's important to preserve this part of history because it speaks so much to the people who made Chicago great and the reasons that this city became such an amazing place.

- [Narrator] And though the industry has evolved and the landscape has changed, you still don't have to look too hard to see the telltale signs of the candy capital.

- At risk of invoking my wife's wrath, I'd go down to a drugstore and pick the candy bars there and say, "This one, and this one, and this one, and this one, and this one.

They were all made in Chicago, comma, once upon a time."

(lively music) (lively music continues)

Behind the Scenes at the Tootsie Roll Factory

Video has Closed Captions

Explore Chicago’s role as the candy capital and visits the Tootsie Roll factory. (3m 24s)

Video has Closed Captions

The Mars family was behind the biggest candy bars of all time, but it came at a cost. (4m 55s)

Video has Closed Captions

The Curtiss Candy Company had a hit on its hands with Baby Ruth. (2m 21s)

The Sweet Treats of the World’s Fair

Video has Closed Captions

The World’s Fair was behind some well-known sweet treats. (2m 56s)

Video has Closed Captions

William Wrigley never intended to make his fortune in candy. (4m 13s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Chicago Stories is a local public television program presented by WTTW

Leadership support for CHICAGO STORIES is provided by The Negaunee Foundation. Major support for CHICAGO STORIES is provided by the Elizabeth Morse Genius Charitable Trust, TAWANI Foundation on behalf of...