The Improvisational Garden

Special | 49m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Patrick Smith uses principles of improv comedy to create a sustainable garden.

Garden design consultant Patrick Smith explains how to create a sustainable garden through the principles of improv comedy. Introducing native plants to a garden can be fun: it allows freedom of expression and the discovery of how to apply naturalism and sustainable beauty to a property.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

University Place is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

The Improvisational Garden

Special | 49m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Garden design consultant Patrick Smith explains how to create a sustainable garden through the principles of improv comedy. Introducing native plants to a garden can be fun: it allows freedom of expression and the discovery of how to apply naturalism and sustainable beauty to a property.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch University Place

University Place is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Experts share horticultural research and gardening tips for Midwest growers. Discover techniques on topics from vegetables and native plants to beekeeping and sustainable landscaping. These talks help gardeners of all levels create beautiful, productive and ecologically sound spaces at home and in their communities.

Video has Closed Captions

Cora Borgens explains why and how to prune woody plants for optimal plant health. (50m 56s)

Indoor Gardening for Food and Fun

Video has Closed Captions

Victor Zaderej offers practical advice on how to easily grow produce indoors. (49m 6s)

Wonderful Wool for Your Plants and Your Planet

Video has Closed Captions

Elaine Becker and Karen Mayhew describe how wool is a healthy soil alternative to peat. (48m 2s)

New and Unique Plant Varieties

Video has Closed Captions

Horticulture specialist Allen Pyle showcases standout plants from 2024 trial gardens. (45m 16s)

Video has Closed Captions

Rachel Belida presents ideas for creating a seven-layer food forest in your yard. (45m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

Becky Gutzman shows how to safely preserve your summer garden bounty for the rest of the year. (58m 35s)

Simple Steps to a Beautiful Rose Garden

Video has Closed Captions

Diane Sommers shares suggestions on growing roses for the home gardener. (47m 50s)

Video has Closed Captions

Alena Joling explains how to take care of your bladed garden tools. (50m 25s)

Preventing Bird-Window Collisions at Your Home

Video has Closed Captions

Brenna Marsicek explains why birds hit windows and how to make windows more bird-safe. (48m 47s)

Legacy Trees and the Prairie Savanna Project

Video has Closed Captions

Matt Noone and Cindy Becker introduce two Dane County area community science projects. (48m 14s)

Video has Closed Captions

Lisa Johnson offers best practices and tips for successful container gardening. (50m 16s)

Video has Closed Captions

Johanna Oosterwyk explores the promise and pitfalls of vertical farming. (50m 58s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

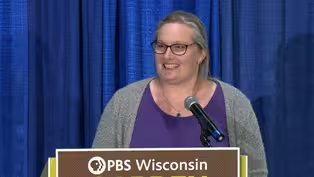

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship- Patrick Smith: Good morning, everyone.

My name is Patrick Smith, and I'm here to talk about my gardening journey over the last nine years, from complete gardening novice to someone who dares to stand here and call themselves a gardener.

You see, I believe the stories that we tell about our gardens, our successes, our failures, our challenges, even our happy accidents, are more powerful when they're more personal.

So, thus, "The Buckthorn Diaries," which is the story of me and my garden, which we jokingly call Buckthorn Acres.

And this chapter, which I'm calling "The Improvisational Garden," it was my journey to discovering sort of my gardening style, if you will.

And it's really, when I say gardening style, I'm calling it improvisational.

But what does that really mean, improvisational?

Well, think of a trumpeter who does a riff of a solo in jazz, or maybe a cook who goes to their refrigerator, finds whatever is there, and makes a delicious meal, or maybe a speaker who is on their way to their presentation and loses their notes.

They give the presentation and it turns out great, even better than the last time they did it.

These are all examples of improvisation, and I think we as gardeners could use a healthy dose of this kind of thinking.

It's like doing improv comedy, which I do, where you step on the stage not knowing what is gonna happen.

And whatever happens, you say "Yes," and then you add to it.

"Yes, and" is the first rule of improvisation.

And in a similar way, you take what Mother Nature gives you and you say, "Yes, and."

You say, "Yes, I have clay soil, and I'm going to plant plants that thrive in clay soil."

Or, "Yes, I have dry shade, and I'm gonna find plants that love those conditions."

It's kind of what happens after you try to control all the elements of your garden and realize that it's futile.

And you realize, no matter how hard you work, that perfection is a little boring and that really staying in the present moment, accepting reality, saying, "Yes, and," is gardening.

Hell, it's, heck, it's living.

Ultimately, it should all come together in a way that reflects the time, the place, the environment, of course, the plants.

But more importantly to me, it includes you and should be the ultimate reflection of you.

Your strengths, your successes, your point of view.

That, to me, is the most beautiful garden.

And it's a garden that no one else can create but you.

Now, I begin my improvisational gardening journey with very, very humble beginnings, with what I call "what's left in the fridge."

We bought our house in September of 2015.

We had lived in the city for decades.

We wanted more space, we wanted more nature, and we wanted more dogs.

We were dog people.

And all of that seemed possible here.

And we just thought, "Grass, good.

Trees, good, woods in the back, good."

We thought we'd plant a vegetable garden, maybe grow some plants.

Other than that, though, we knew nothing.

The first thing that came to mind was "mullet house."

We had a big, beige, bland, boring house in the front and a bunch of wild in the back, so business in the front, party in the back.

And really, for nine years, I've gone with that theme rather than a particular style.

Ideas have come and gone, but the very first morning we woke up in the new house, got our coffee, and went to the windows to look out at the back of the property, we saw this.

A 40-foot spruce had just fallen over on the patio in the middle of the night, as if it had just given up in the middle of the night.

[audience laughing] What should have been a warning, we took as a wake-up call.

It was time to get to work.

In hindsight, we were comically naive.

So cue the tiny violin.

Once we saw that, we started to see what we had really purchased: a whole lot of nothin'.

And what was there was old and tired and worse for the wear.

In fact, if you look in the upper left-hand corner of that photo, those flowers are plastic lotuses... [audience laughing] ...floating in the water feature.

[audience laughing] Ah, the truth is, I didn't follow that warning.

I immediately started planting what I thought I knew.

I planted perennials all fall and into the next year with no plan.

And it wasn't until I was in the middle of reading the latest coffee table gardening book that I thought would really help me that I realized I was in way, way over my head.

Luckily, in that same book, I came across the name of Roy Diblik of Northwind Perennial Farm.

Some of you may know him or know of him.

Thank God I came across that name.

And, in fact, I just picked up the phone and immediately called.

It took a few phone calls, but Roy Diblik showed up at my front door and we took a tour of our property.

And Roy, as kind and humble as he is, looked at me at the end of the tour and said, "Patrick, you do know you bought five acres of invasive plants, right?"

[chuckling] I almost burst into tears.

[laughing] And we had.

Well, it wasn't quite five acres.

We bought four acres of invasive plants, five acres of diseased and dying trees, and a whole lot of turf grass and bark mulch.

That began my real journey towards becoming a gardener.

From that moment-- Oh, sorry.

From that moment, I knew we had to remove those groves of buckthorn and invasive honeysuckle, along with all those diseased and dying trees.

Out came ash and pine and spruce, two beautiful specimen trees that were splitting down the middle, and this arborvitae that looked like it was slowly eating the house alive.

And inside that arborvitae was the back door to the house that they had just continued to carve out a hole for.

Yeah.

Well, all that, you know, sounds easy, but it was difficult, expensive, and a little traumatic because many of the trees were part of the reason we bought the property in the first place.

And with the trees went a lot of my excitement.

Long term, I was emboldened, but that took years.

And after that first wave of tackling all the invasive trees and woody invasives, I mean, the dying trees and woody invasives, guess what?

We set the table for the onslaught of herbaceous invasives.

You name it, we got it.

Purple nightshade, garlic mustard, creeping Charlie.

I could go on.

Name a weed or an invasive, we probably had it.

And I learned that there wasn't really gonna be an end to that, that there would be subsequent waves of plant deaths and invasives, and that I was going to have to spend time and money and effort to continue to basically keep them pushed back, because I think many of you know, we never really get rid of those things.

We're always, again, kind of trying to find that balance between what we can live with and how aggressive they can be.

Now, during that whole period of erasing the chalkboard, I began to really take stock, to ask myself the harder questions, like, "You do know you don't know what you're doing?"

And, "Why am I doing this?

"What do I need to learn?

Who can I get help from?

What inspiration do I have?"

And that is really the point at which I realized that inspiration is everywhere, and that the whole rest of my life could inform what I was doing in the garden.

And I had not made that connection.

And I knew that I could find mentors and get educated, 'cause up to that point, I had been doing internet searches, which we know everything's true on the internet, and buying fancy coffee table books.

And I just was more confused.

So I started looking and looking back in the past, looking at photos I had taken over the years.

And I suddenly realized, I am, I'm starting my improvisational journey.

And that was the birth of my improvisational gardening approach.

I started looking at places that I'd been.

I've been very fortunate to spend a career traveling around the world.

And I started going through old photos and realized I had taken as many pictures of art and gardens and other things than the actual work I was supposed to be doing.

[laughing] And all of a sudden, I'm like, "Wait, wait a minute.

"I'm surprised I've taken these pictures of gardens that, you know..." I had never connected to the fact that now suddenly I want to be a gardener.

And every place has been a source of inspiration.

And I've also lived across the country.

And so from Seattle, Washington, to New York City, from Kansas City to Nashville, from Atlanta to Milwaukee, I really started to see that there was a lot of inspiration and a lot of things that could inform what I was doing.

And even to this day, a lot of the plants I've chosen are subtle, well, and not-so-subtle reminders of the places I've been.

And I remembered a quote that I loved from Diana Vreeland, who was a former editor of Vogue magazine, and she said, "The eye has to travel."

And when you think about that, our eye is our dominant sense.

It's not just the way we see the world, it's the way we perceive the world.

It's the way we navigate the world.

We are predisposed to connect the dots.

Now, my work background is a whole other story.

I spent 32 years in fashion merchandising, in product development and design.

And I, you know, when I retired, I thought that was the past, and I was looking forward to discovering what my interests were.

I didn't think it had a connection to gardening at all.

But just one simple example.

You know, in my fashion merchandising career, you know, we developed an item that became an outfit that became a wardrobe that had seasons, that balanced style versus trend.

Hmm.

You buy a plant, you group it with other plants, becomes a bed, becomes a garden, is part of a landscape that has seasonality that you balance style versus trends.

Wow, maybe I can take the tools that I thought I couldn't use and just use them in a different way in my garden.

I started to show up in my garden.

And I'm just gonna show you a few photos.

First, I just made visual connections.

A photo I had taken of a men's shirt display in New York, suddenly I visually connected it to a display of tulips I saw in downtown Chicago.

Then I started making real connections to the plants.

This women's jacket, when I saw these Crispa tulips, I remembered the trim on that jacket.

I was starting to connect the dots.

This custom motorcycle paint that I saw at a rally inspired me to use those colors in this planter.

And this piece of folk art I saw in Puerto Vallarta showed up in the color story we used in our front yard.

And lastly, and kind of sentimentally, I came across this picture I'd taken of a custom dress, and the skirt reminded me of my grandmother's prized tulips that she was obsessed with, which inspired me to plant the only tulips-- I mean, the only roses I have in my garden.

And to me, that was kind of a full-circle moment when I realized that, you know, the whole art inspires us, which inspires the art.

Now it's in the garden.

And finally, from an education perspective, thank God I finally found the Master Gardener Program.

UWM Master Gardener Program was so critical for me because it's based in science and evidence-based information.

And after all that searching and YouTubing and buying all these books and being very confused, I found I could really have a framework to judge what worked and didn't work, or that I could really learn, try and learn and apply.

That was really the critical thing.

But I also loved the volunteer part.

And I have to say, I don't know that I would even be standing up here today if it wasn't for the people that I volunteer with at Lynden Sculpture Garden in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

They're a big part of the reason I'm even here today.

But then I thought, my earliest memories of gardens and gardening, which I felt almost detached from, my grandparents.

Talk about differences.

Grandma and Grandpa Smith were, it was like a Rockwell painting.

The white clapboard house, the big vegetable garden, Grandma's prized cherry tree in the front yard that we just completely decimated, and all of her bachelor buttons around the root cellar.

Contrasted with Grandma and Grandpa Schnoebelen, my German grandparents who lived in the city, and everything was perfect and orderly, and we were free labor for that garden.

[all laughing] But it was beautiful and aspirational.

And then finally, I thought of my dad, who, even though he'd grown up on a farm, came late to gardening.

And I think when I look back on it, that that was probably because after raising nine kids, it was probably the one place where he felt not only at ease, but a little bit more in control.

Now, of course, I was inspired by other gardeners, and since I loved perennials, I'm not even sure why I was so drawn to them, I was drawn to the people I call The New Perennialists.

So on the left here, you see Piet Oudolf, who is arguably one of the most famous garden designers in the world right now.

He did the Lurie Garden in Chicago, the High Line in New York.

And I loved the depth and complexity of his naturalistic plantings, and that he said a garden is beautiful in every season, and that brown, just like whatever other color is your favorite color, is a color, too, in the garden that can be used to effect.

The center photo is a garden that was designed by a firm called Oehme van Sweden, and they pioneered the use of ornamental grasses.

Well, for a kid from Kansas to look at designed garden like this that not only didn't rely on a tremendous amount of flowers, but flowed right into the land and to the farmland beyond, it reminded me of growing up as a kid and driving through the tallgrass prairie in Kansas.

I was really now, you know, getting going with this idea that you could find inspiration everywhere.

And finally, on the far right, you see Roy Diblik, who I call my Yoda of gardening.

He is just literally the most humble man you'll ever meet, and you'll learn more from him in a casual conversation than any number of gardening videos.

His idea of plant communities, I'm just beginning to understand in my own garden, and the fact that you can start simply with three to five plants and learn how plants really grow and how they live together, and just keep building on those three to five plants.

And finally, he calls sedges "living mulch."

And I am now officially obsessed, and I hope nobody ever finds out how many I have put in my property.

Inevitably, this led me to the newest sources of inspiration for me: a group of gardeners I call The New Naturalists.

And these are just three examples.

There are tons more.

I encourage you to go and find out more about these folks.

I picked these three because they really represent really such a dynamic and diverse approach to what gardening is all about right now.

And call it ecological horticulture for the fancy term, call it naturalistic, call it sustainable, but that's what they're doing.

That's what they're pioneering.

Doug Tallamy, I call him The Professor.

He is a professor of etymology, and he helped create HomegrownNationalPark.org, which has a lofty goal of encouraging all of us to plant more natives in our yards, up to half of your property in natives.

And if we did that, not only would it be the biggest national park in the United States, it would actually be the size of about 10 of them put together.

And all they're asking us to do is invite nature into our, back into our properties, where it used to belong.

He also pioneered the idea, and I love this, of keystone plants, plants that punch above their weight, plants that interact with more living things than most of us could imagine.

And for him, the oak tree is the perfect example.

One oak tree in your yard interacts with over 500 different microorganisms: caterpillars, birds, mammals.

That's a heck of a lot more than that green ball of a burning bush in the front yard that, for a couple of weeks in the fall, kind of turns red 'cause it's ashamed that's all it can do.

[audience laughing] Now, I don't mean to be so mean to-- If you have a burning bush, by all means, keep it.

But maybe add to it and add something that really does interact, you know, that promotes life.

Kelly Norris, this is his garden in the center in Des Moines, Iowa.

He used to be the director of the Des Moines Botanical Garden.

He is now a private designer for both public and private gardens.

And I call him The Artist, because when I look at that, it looks like an impressionist painting.

And it's deceptively simple, but really complex in its planting.

And I just think that's amazing that that's all native plants.

And finally, Benjamin Vogt, I call him The Activist because, like me, he came to gardening pretty late.

He was a journalist and a writer.

He lives in a suburb of, in Nebraska in a subdivision.

And when he discovered native plants and sustainability, he went deep.

He doesn't look at just the history of the lawn in America, but the sociological impact and all the other elements that got us to the place we are today, where our lawn is a thing that takes up so much of our time and resources, but doesn't really interact with much.

His quote is, "Prairie up" and "Un-lawn America."

And, you know, between the three of them, I really began to learn and accept the reality that we are living in the era of environmental gardening.

Many of you may know that, maybe.

I'm sure many of you are farther along that journey than I am.

And just, you know, let's just acknowledge we have a biodiversity crisis.

We have a climate crisis.

And not to get into science or anything, just, if you're a gardener, surely you know things have changed.

At least I know in nine years, I've already had a zone change, and I think there have been three in my lifetime.

I know my winters are a little drier.

I know the rest of the year is unpredictable, and it's almost always on the edge of a drought, if not in one.

That's certainly not the way it used to be.

But I love the way gardeners in particular are rising to the challenge.

They're trying new things, they're talking to each other.

Things that used to be kind of separate, horticulture, ecology, are starting to merge.

And I think we're all starting to realize that a lot of what we've learned and a lot of what we do in our gardens is kind of counterintuitive to how nature actually works.

And that's where I sort of began to make my connection to sustainability.

I mean, I've come late to the party and I've got a lot to learn, but it really resonated with me, this idea that you show up, you accept reality, and you add to it based on what you've learned.

You observe nature, you partner with nature, just like I go on the stage and partner with the person across from me, and create reality together.

I looked up the definition of sustainability, and you can read it here, what it entails.

And I thought, the words may be different, but when I think about what improvisation means to me, sustainability, improvisation both are about accepting reality, being in the present, working with and not against, less control and more partnership, and accepting the unexpected.

Now, I also realized that sustainability really entails all the things we already are familiar with as gardeners.

You can read this list.

You know, we all know soil health, water efficiency, plant selection.

I won't read the whole list.

I'll just give you one example to me where I think sustainability is just looking at our gardens through a different lens, and that resonated with me: soil health.

I learned very early on as a master gardener to get a soil test.

And I think everyone should.

They're really helpful.

But what I noticed is that when you get your soil test, it tells you, you know, what your soil composition is, but it also has all sorts of recommendations.

You know, it might be low in nitrogen, or you might need phosphorus.

It's very alkaline or it's very acidic, implying that we should all do something to make it better.

Through the lens of sustainability, I look at it now and go, "Do I really need to do anything?"

I mean, this is just what my soil is, right?

And when I think about Mother Nature, doesn't she have a solution for just about every situation and condition?

So maybe before I put that shovel in the ground-- which, by the way, gardening is disturbance.

Before I disturb, maybe I should think twice and not think that I have to change everything so much.

And I could kind of get behind that.

I kind of simplify sustainability into just nature-driven decision-making.

And I can get behind that.

Plant more plants?

I'm in.

You know, I'm literally at probably about the 27th stage of gardening addiction.

So plant more plants?

Good for me.

Plant 'em closer together?

I'm in.

Plants are social, and they live in community.

They literally lean on each other and support each other.

And my favorite, no plant ever evolved to grow in bark mulch.

It doesn't rain down from the sky.

There isn't a special season where it shows up.

Plants actually go through last year's debris.

And I could get behind that because, again, like I said, gardening is disturbance.

And guess what?

Mother Nature's response to disturbance is what we call weeds.

They're early colonizers, they're first responders.

And so we have to learn that if we're gonna disturb, let's make it a beautiful disturbance.

And let's use some of her tools, like native annuals, to get a jump on the "weeds" that we don't want in our gardens.

Essentially, to me, sustainability is just conscious stewardship.

And stewardship, but not ownership.

And dynamic, alive, not static.

Integrated, not isolated like that burning bush.

Responsible beauty, not just pretty.

Like, what is it contributing?

You're beautiful, but what else can you do for me?

And collaboration, finally, which is the key to improvisation.

Collaboration, not control.

So after all that, it was time for me to really get to work, to kind of almost begin again, although I never stopped working in the garden this whole time, but to really get clear about my priorities and what I wanted to accomplish.

It became easy after that.

My goals are simple and straightforward.

I want responsible beauty, not just pretty.

I don't want to just plant more native plants, which is where I'm at right now.

I don't pretend to be far along in this sustainable journey, but I really feel good about getting on board and celebrating native plants.

And I've learned the hard way from so many failures that the more botanically diverse my garden is, the more it can withstand whatever comes my way.

Because I've planted those dozens of ninebark cultivars and watched powdery mildew destroy them.

I've planted a hedge of viburnums and watched viburnum leaf beetle eat them alive.

So now, as my garden becomes more diverse, even if something bad does happen, it's not as dramatic.

Everything else can lift the weight while that recovers, and I can go about the business of doing more fun things.

I want to be curious, I'm naturally curious.

I love taking chances and being responsible for my mistakes, but I actually want to cultivate curiosity.

I decided to devote several beds in my garden to just finding out what happens.

I call one the Island of Misfit Toys.

And the other one is literally the nursery, just to see how these things grow before I spend a ton of time and effort and money on them.

And finally, I want to leave the land healthier than I found it, which, by the way, is my easiest goal, because as I told you, when you start with five acres of invasive plants, you have nowhere to go but up.

[audience laughing] My gardening style maybe will always be a hodgepodge.

I've used words like naturalistic and aspirational and experimental, but at the end of the day, I landed on improvisational.

Accepting what you have, adding to it, learning and experimenting based on knowledge.

Really, it's 10 pounds of flour in a 5-pound bag.

But improvisational is where I kind of landed and where I feel most comfortable.

My plant, I love planting themes.

These are my planting themes: joy and abundance, plant communities, transition to natives, and you see this connection to all the things that I really spent time sitting with and figuring out what kind of resonated with me.

Joy and abundance, to me, say what you will, I look at that and everything is alive.

The climbers are climbing, the bloomers are blooming, the trees are treeing and the shrubs are shrubbing.

Here is more abundance, but here it's really, this is a community of plants that probably has done better than any number of beds in my garden.

They're really happy together, and they're, it's about half natives.

I'm trying to get to about 70%.

Some are from Roy Diblik's appropriate perennial plant list, and a few are just because they mean something to me.

I call this the Granny Garden because a lot of them are more old-fashioned, and also because there are some favorite plants.

There are peonies in there that remind me of one of my grandmothers.

There are a few daylilies that remind me of my mom.

This cultivar, this photo, pardon me, is of cultivars that are turning into more native plants.

Obviously, the spruce tree is not a native, but it has a home 'til it dies.

And we're already starting to plant other trees that are native to take up the mantle when it's gone.

The ironwood tree in the foreground is native, and those ninebarks you see are gone and have been replaced with more native plants.

And finally, happy accidents.

These orange daylilies were not my friends.

I thought I got rid of them.

I planted a hedge of hydrangea.

And, no, they come up every year stronger than ever, and for about three weeks in August, they're beautiful.

I call it the creamsicle border, and I had nothing to do with it, but I take full credit.

[audience laughing] On the right, nothing but green.

But every time I look out the window, it's just so calming to me, even though from a design perspective, it really doesn't make any sense.

My planting priorities are straightforward, too.

Now, I plant nothing but native trees and shrubs, not just for structure, it's legacy, because I know that there's no way I can handle an entire landscape of perennials as I get older.

Trees and shrubs are my friends.

And perennials, I have to plant more natives because I don't have the time and effort and budget to take care of all of that.

And sedges, you know, Roy sent me down this path and I have not stopped.

I have cut, I'm really proud of the fact that I set a goal of getting rid of half of my turfgrass in seven years.

I did it in five.

And I figure I can probably get rid of another 10% to 15% and still have room for us, the dogs, all the nieces and nephews who come to visit, and our friends and family who visit.

I didn't really need all that.

Once I got started, it just kept going.

And then, I think all of us as gardeners have to draw the line somewhere.

For me, it was annuals.

It just wasn't, you know, I had a big garden.

And so the good news was, is I didn't need a lot of pots and a lot of, and annuals now, and I'm just on the edge of learning about native annuals, things like partridge pea, variations of Coreopsis and Gaillardia and others that I can use for solving problems, filling in things, and they will go away, but they're serving a purpose.

They're my first responders.

Now, I love tonalities.

I learned that in my fashion merchandising career.

But in the garden, I found they could be a good tool for me, for someone who didn't know all the rules of gardening, because they're very forgiving.

And tonalities are just mixes of color, yellow, orange, red, white, green, silver, that are easy on your eye.

And what I found is while I'm experimenting and learning, if I limit my color palette, it almost makes me look like I'm a better gardener than I really am.

So, for instance, in the front of the mullet house, one kind of requirement I came up with was, well, everything has to bloom white.

Now, it can start yellow and turn white.

It can be white and turn pink, that's fine.

But by making it mostly white, no matter how much craziness is going on in any particular bed, it looks pulled together, it looks calm.

And so when people come to visit, it looks like I know what I'm doing.

In the back, I like bolder colors, but instead of doing really a lot of bold, contrasting colors, I kind of stick to yellow, orange, and red.

It kind of is that same tonality, but it's for full sun and it holds up to that.

And blue for me, I don't know why, has never been a favorite color.

Sometimes I think blue flowers look almost unnatural.

Ha-ha.

I had this problem path that I didn't know what to do with, so I challenged myself to use that blue-purple-lavender palette.

And now when I walk down that path, my shoulders actually start to come down.

It's so calming.

Now, the glass of wine in that photo doesn't hurt, but... [all laughing] But I've learned to love the use of tonalities.

And then finally, the ultimate tonality to me is just the power of green.

Not a flower in sight.

And green, while it is green, is everything from almost yellow to almost gray to almost blue and everything in between.

And that's before you even get to structure and color and texture.

To me, this is a journey of tonality I'm gonna be on for the rest of my life.

I think I'm just scratching the surface.

Now, along the way, I developed a couple of tools for me.

They may or may not be helpful for you, but, again, for the first several years of my garden, the property determined my priorities, and it was, I couldn't quite get ahead.

And one day, and I'm not sure.

I'll just chalk it up to improvisation.

I was sitting there with a piece of paper, my property lines, where the house was, trying to figure out, like, how do I get ahead of this?

Where I've been, I was kind of, like, playing whack-a-mole in the property.

And somehow, an old dartboard got involved.

I pulled off the top of it, stuck it over my property, and realized this was how I was gonna prioritize.

The bull's-eye and those first two rings were where I spent most of my time, where I had the most resources, the most access to water, and that would be where I would prioritize.

And everything else had to, the further out it got, the more it had to take care of itself.

Now, that doesn't mean there isn't a lot of work getting it to that point.

But now if I want to keep some of those more exotic plants or things that don't contribute as much, they're near the house.

And I've done a lot of transplanting.

And natives have really given me a leg up on those farther-away areas, that as I establish those communities, they can take care of themselves a lot better probably than I could.

I also came up with what I call my garden building rule of thirds, and I don't know about you, but when I started planting beds and reading what to do, I would slavishly go over these plans and make pretty big investments up front in what I thought it was supposed to do and how the balance between all the things were.

And I realized I wasn't good enough for that to not, for that to be good even in a year or two or three, that I really needed to cut back on the planning by, you know, and it's, now for me, it's about a third, and then a third reacting, and then a third creativity and improvisation.

So what I tend to do now is overplant the ground cover layer so I can get a leg up on weeds.

And in the focal layer, what I call the focal layer, where all the fun, pretty stuff is, I plant less, but more varieties so that I have time to see what happens before I invest, before I go out and get, you know, and make big statements.

But by that third year, and it usually tends to be about a third year, give or take, I'm ready to improvise.

It's like, "Oh, I'm finally gardening.

"I want some more yellow over there.

"And that didn't work, so I'm gonna double down on this."

All the while that that ground cover layer is working for me, and the tree and shrub layer, also, I spend about the same amount of time.

And for me, that's, I've found that to be a good balance.

Now, I'm gonna go quickly through this next section, because I have an obsession with naming my beds, as you've heard me say before.

I have the Granny Garden, the Sunset Landing.

I'm a sucker for a theme.

This is the Pollinator Garden.

This is the Golden Meadow.

This is what I call the Transitional Triangle.

And it kind of holds together because when you go to the left of this bed, it's a whole different thing, and to the right is a whole different thing.

And this is kind of right on the verge of kind of orderly and wild.

And then this is the Hydrangea Haven.

Now, I always thought of hydrangeas being kind of old-fashioned and a little granny and little bosomy.

But I've become obsessed with them.

And now the entire front yard of the mullet house is circled with about 15 varieties of hydrangeas.

And I'm experimenting now with even more native hydrangeas, more arborescens, more quercifolias.

I love it.

Quickly on plant selection, I found, and I think all of us like to save money.

So whether you have a small garden or a big garden, one of the things we used to say in retail was, "NPR: never pay retail."

Now, that's not fully true.

But we always said, "As retailers, "we know everything you want is on sale somewhere.

You just have to find it."

And for me, that became important.

And so I love a past-season sale.

I love a clearance sale, I love a one-day-only sale.

I could probably tell you the promotional calendar of every nursery in a three-county area, because I needed to buy more quantity.

But the price you pay for that sometimes is less-than-healthy plants.

So one of my other rules: don't buy pretty, buy healthy.

And I'm that guy you'll see at the nursery pulling everything out of its pot because I've, and because I usually buy when the plants don't have flowers, because I think many of us know, and I know as a retailer for sure, I promise you this, when that plant is in flower, they're making the most money they're ever gonna make on that plant.

And most of us, pretty quickly as gardeners, learn that we don't need to see the flower to know whether it's a healthy plant or not.

So I'm pulling it out.

Do I see the roots even?

Are they rotted, are they root-bound?

Are they moldy?

And in some cases, especially with big box stores, is it a little plug they put in a big pot, and the root system hasn't even developed yet?

Finally, I had to control myself 'cause I'm an impulse buyer.

So I literally keep a pocket plant list in my pocket all the time when I go to nurseries to try to keep myself on track.

It doesn't always work, but I do.

And then finally, learning about keystone natives really helps me to focus on those, 'cause I know I'll get more bang for my buck with those than I would with other plants.

I love the turn of a phrase, so I will try to go quickly through this, too.

You've heard some of these.

I'm a big believer in the eye has to travel.

We love connecting dots, that's how we see the world.

I love this phrase: "Without a gardener, there is no garden."

Gardening is disturbance.

Make it a beautiful one.

Take responsibility.

This was our Smith family motto when I was a kid.

And I'll be honest, I'd forgotten it.

"Live with it, learn from it, build on it."

And it so fits nicely to me with my improvisational piece of live with it, accept reality, learn from it, add to it, and then build on it.

How you do anything is how you do everything.

That's a Buddhist phrase that I heard, and it's so true.

If you look at your life, you know, your hobbies, what you do for a living, everything, it's kind of how you do everything is how you do anything.

And what I didn't want to do was spend so much time trying to fix everything that was wrong.

I wanted to spend more time doing what I was good at.

And I think that's true in the garden too.

And finally, and this is mine, the future is a place we are making right now.

Every plant you plant, every seed you sow, you are creating your own future in the present.

And I think that's so important because I know that I have had those days where I just don't want to think about it.

I don't want to deny, I just don't want to deal.

But that means then, that the future will show up and smack me upside the head.

And I love knowing that I get to decide every day the future I'm planting.

Now, these last few slides are just some tips that I use that may be helpful for you, and I, there are three.

One, I'm gonna go over some improvisation tips, some sustainability tips, and a little about good neighbor gardening.

So these are the slides, I'll kind of read more than I have up to this point.

The first rule of improv, always say "Yes, and."

And what that means in the garden is work with what Mother Nature gives you.

Add new information.

That's the other, the next rule of improv.

And that really means make sure your garden reflects you.

Then there is, then you're beyond judgment.

Doesn't matter what anybody says.

What's the one phrase I love?

"What you think about me is none of my damn business."

I love that.

[audience laughing] And it's kind of like, what you think about my garden is none of my damn business.

I love my garden.

And every garden I visit, you can tell when it reflects the person that has created it.

And when, like in my early years, when it looks like somebody else's idea.

Be present.

Don't block or deny.

Embrace the reality of what you're working with, whether it's a large or small garden, whatever your budget is, whatever your plants are, it will be beautiful the more you show up in it.

Understand the location and relationship.

In improv, it's like, who have I been identified as?

Where are we, what are we doing?

In the garden, it's not just that I live on this street or in this neighborhood, but, like, I found out that my subdivision had been a pig farm.

Well, what does that mean about my soil?

And, you know, and then I was, I found out what my ecoregion was and what plants used to grow there, and maybe they still could.

And then finally, you look good if you make your partner look good on stage.

Much the same way that you look good if you make Mother Nature look good.

From a sustainability perspective, these are just five.

And I promise you, there's dozens.

But these tips really resonated with me.

And to me, they're very straightforward and simple.

Reduce your lawn if you can.

Think area rug, not wall-to-wall carpeting.

Remove invasive plant species.

Learn what they are.

Now when I say remove, it sounds like they're gone forever.

We all know better than that.

But do your best.

That's what I do.

Rethink pretty, I've said it a few times.

Expect more from your plants.

Look for responsible beauty.

Plant for pollinators.

Really, just plant for living things and really identify and plant keystone plants.

And finally, and my favorite, start planting, even if it's one native plant or one new.

And then if it works, just keep planting more.

And if it doesn't, just keep planting anyway.

Plant generously because plants love to live in community.

Oops.

And then finally, what I've noticed in my own garden and kind of as I've driven through other areas to seek inspiration is that when I started down this native journey, it could look like a hot mess really fast.

And if you live in an urban area or a subdivision or the suburbs and you're dealing with HOAs or neighbors who love to have an opinion about everything, these are just a few tips to keep your garden from being perceived as weedy or unruly.

Limit your plant palette by square footage.

The smaller the space you have to work with, limit the varieties of plants.

It will look more orderly.

Use borders and ground covers.

And I use borders more now than ever.

I can take those sedges and not just use them as a ground cover, but use them as a border.

And suddenly, the same person can look at this bed without a border and this bed with a border and think, "Wow, that really looks like he knew what he's doing."

You know, I love the phrase Kelly Norris uses called "orderly frames."

The minute you have borders or pathways or a good ground cover layer, people perceive it as orderly.

Also, maybe stick with only one to three plants that are in bloom at any given time, because that's, again, easy on the eye.

And then, you know, another one to three each season.

And really think in the front yard if you're, especially if you're in a smaller area, about keeping those plants no more than maybe three to four feet high and in the middle or the back.

And it seems simple, but really, your eye does travel and it goes until it's stopped.

And if it stopped in the front, you're like, "What's wrong?"

If it doesn't stop and it goes up to the house and keeps going, it's at ease.

The eye just signals the brain that everything's okay.

And these, I think, and then, of course, repeat, repeat, repeat.

Using fewer varieties and fewer colors, or fewer plants in bloom, just creates a sense of ease and not so much masses, but drifts and ways that your eye can connect those dots.

The neighbors will lean in instead of wondering what you've done or calling the HOA.

Now, I'm near the end of the presentation, and I wanted to leave you guys with this because I know, over the years, one of my old goals was sort of, like, keeping things alive.

You know, I remember one quote that's like, "Maybe it's not so much how many plants die in your garden, but the fact that so many actually live."

And another quote I love, and I'll share this with you, is 'cause I've been always kind of more obsessed with, "Will it live and how long will it live," and all that.

Well, I love this quote and I'm gonna read it.

"Perhaps the gardener is not someone "who makes forms last over time, but over time, if possible, ensures that enchantment survives."

And what I love about that is you're the enchantment.

That that's what we bring to the garden.

Not so much that we got more to live than die.

Not so much anything other than, "It couldn't have been anybody else's garden but ours."

That is the end of my presentation.

My name is Patrick Smith again.

Stay curious and have fun.

Questions?

[audience applauding]

Support for PBS provided by:

University Place is a local public television program presented by PBS Wisconsin

University Place is made possible by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.